by Maria Popova

“It is impossible to find an answer which someday will not be found to be wrong.”

“If we ever reach the point where we think we thoroughly understand who we are and where we came from,” Carl Sagan wrote in his timeless treatise on science and spirituality, “we will have failed.” Perhaps because, as Krista Tippett has astutely observed,

“If we ever reach the point where we think we thoroughly understand who we are and where we came from,” Carl Sagan wrote in his timeless treatise on science and spirituality, “we will have failed.” Perhaps because, as Krista Tippett has astutely observed,science and religion “ask different kinds of questions altogether,

probing and illuminating in ways neither could alone,” some of

humanity’s greatest scientific minds have contemplated the relationship

between these two modes of inquiry — Galileo in his legendary letter to the Duchess of Tuscany; Ada Lovelace in her meditation on the interconnectedness of everything; Einstein in his answer to little girl’s question about whether scientists pray; Jane Goodall in her poetic take on science and spirit; Sam Harris in his elegant case for spirituality without religion; and physicist Margaret Wertheim in turning to Dante for an answer.

Among the tireless investigators of this duality is legendary physicist and science-storyteller Richard Feynman (May 11, 1918–February 15, 1988), who explores this very inquiry in the final essay in The Pleasure of Finding Things Out: The Best Short Works of Richard P. Feynman (public library) — the same spectacular compendium that gave us the Great Explainer on good, evil, and the Zen of science, the universal responsibility of scientists, and the meaning of life.

Feynman writes:

I do not believe that science can disprove the existenceClarifying that by “God” he means the personal deity typical of

of God; I think that is impossible. And if it is impossible, is not a

belief in science and in a God — an ordinary God of religion — a

consistent possibility?

Yes, it is consistent. Despite the fact that I said that more than half of the scientists don’t believe in God, many scientists do

believe in both science and God, in a perfectly consistent way. But

this consistency, although possible, is not easy to attain, and I would

like to try to discuss two things: Why it is not easy to attain, and

whether it is worth attempting to attain it.

Western religions, “to whom you pray and who has something to do with

creating the universe and guiding you in morals,” Feynman considers the

key difficulties in reconciling the scientific worldview with the

religious one. Building on his assertion that the universal responsibility of the scientist is to remain immersed in “ignorance and doubt and uncertainty,” he points out that the centrality of uncertainty in science is incompatible with the unconditional faith required by religion:

It is imperative in science to doubt; it is absolutelyIn a sentiment that calls to mind Wendell Berry on the wisdom of ignorance, Feynman adds:

necessary, for progress in science, to have uncertainty as a fundamental

part of your inner nature. To make progress in understanding, we must

remain modest and allow that we do not know. Nothing is certain or

proved beyond all doubt. You investigate for curiosity, because it is unknown,

not because you know the answer. And as you develop more information in

the sciences, it is not that you are finding out the truth, but that

you are finding out that this or that is more or less likely.

That is, if we investigate further, we find that the statements of

science are not of what is true and what is not true, but statements of

what is known to different degrees of certainty… Every one of the

concepts of science is on a scale graduated somewhere between, but at

neither end of, absolute falsity or absolute truth.

It is necessary, I believe, to accept this idea, not onlyBefriending uncertainty, Feynman argues, becomes a habit of mind that

for science, but also for other things; it is of great value to

acknowledge ignorance. It is a fact that when we make decisions in our

life, we don’t necessarily know that we are making them correctly; we

only think that we are doing the best we can — and that is what we

should do.

automates thought to a point of no longer being able to retreat from

doubt’s inquiry. The question then changes from the binary “Is there God?” to the degrees-of-certainty ponderation “How sure is it that there is a God?” He writes:

This very subtle change is a great stroke and represents a

parting of the ways between science and religion. I do not believe a

real scientist can ever believe in the same way again. Although there

are scientists who believe in God, I do not believe that they think of

God in the same way as religious people do… I do not believe that a

scientist can ever obtain that view — that really religious

understanding, that real knowledge that there is a God — that absolute

certainty which religious people have.

A 1573 painting by Portuguese artist, historian, and

philosopher Francisco de Holanda, a student of Michelangelo's, from

Michael Benson's book 'Cosmigraphics'—a visual history of understanding

the universe. Click image for more.

outweighs but doesn’t displace the degree of doubt — in the scientist,

unlike in the religious person, doubt remains a parallel presence with

any element of faith. Feynman illustrates this sliding scale of

uncertainty by putting our human existence in cosmic perspective:

The size of the universe is very impressive, with us on aWith an eye to the immutable mystery at the heart of all knowledge — something Feynman memorably explored in his now-iconic ode to a flower — he adds:

tiny particle whirling around the sun, among a hundred thousand million

suns in this galaxy, itself among a billion galaxies… Man is a

latecomer in a vast evolving drama; can the rest be but a scaffolding

for his creation?

Yet again, there are the atoms of which all appears to be

constructed, following immutable laws. Nothing can escape it; the stars

are made of the same stuff, and the animals are made of the same stuff,

but in such complexity as to mysteriously appear alive — like man

himself.

It is a great adventure to contemplate the universeBut even if one comes to doubt the factuality of divinity itself,

beyond man, to think of what it means without man — as it was for the

great part of its long history, and as it is in the great majority of

places. When this objective view is finally attained, and the mystery

and majesty of matter are appreciated, to then turn the objective eye

back on man viewed as matter, to see life as part of the universal

mystery of greatest depth, is to sense an experience which is rarely

described. It usually ends in laughter, delight in the futility of

trying to understand. These scientific views end in awe and mystery,

lost at the edge in uncertainty, but they appear to be so deep and so

impressive that the theory that it is all arranged simply as a stage for

God to watch man’s struggle for good and evil seems to be inadequate.

Feynman argues that religious myths remain a valuable moral compass, the

basic ethical tenets of which can be applied to life independently of

the religious dogma:

In the end, it is possible to doubt the divinity ofHaving grown up in communist Bulgaria — a culture where blind

Christ, and yet to believe firmly that it is a good thing to do unto

your neighbor as you would have him do unto you. It is possible to have

both these views at the same time; and I would say that I hope you will

find that my atheistic scientific colleagues often carry themselves well

in society.

nonbelief was as dogmatically mandated by the government as blind belief

is by the church elsewhere — I find Feynman’s thoughts on the dogma of

atheism particularly insightful:

The communist views are the antithesis of the scientific,He revisits the ethical aspect of religion — its commitment to

in the sense that in communism the answers are given to all the

questions — political questions as well as moral ones — without

discussion and without doubt. The scientific viewpoint is the exact

opposite of this; that is, all questions must be doubted and discussed;

we must argue everything out — observe things, check them, and so change

them. The democratic government is much closer to this idea, because

there is discussion and a chance of modification. One doesn’t launch the

ship in a definite direction. It is true that if you have a tyranny of

ideas, so that you know exactly what has to be true, you act very

decisively, and it looks good — for a while. But soon the ship is

heading in the wrong direction, and no one can modify the direction

anymore. So the uncertainties of life in a democracy are, I think, much

more consistent with science.

guiding us toward a more moral life — and its interplay with our human

fallibility:

We know that, even with moral values granted, humanNoting that all three aspects of religion — metaphysical divinity,

beings are very weak; they must be reminded of the moral values in order

that they may be able to follow their consciences. It is not simply a

matter of having a right conscience; it is also a question of

maintaining strength to do what you know is right. And it is necessary

that religion give strength and comfort and the inspiration to follow

these moral views. This is the inspirational aspect of religion. It

gives inspiration not only for moral conduct — it gives inspiration for

the arts and for all kinds of great thoughts and actions as well.

morality, and inspiration — are interconnected and that “to attack one

feature of the system is to attack the whole structure,” Feynman zeroes

in on the inescapable conflict between the empirical findings of science

and the metaphysical myths of faith:

The result … is a retreat of the religious metaphysicalAnd so we get to the most enduring challenge — the fact that, in Tippett’s words, “how we ask our questions affects the answers we arrive at.” Arguing that science isn’t aimed at the foundations of morality, Feynman writes:

view, but nevertheless, there is no collapse of the religion. And

further, there seems to be no appreciable or fundamental change in the

moral view.

After all, the earth moves around the sun — isn’t it best to turn the

other cheek? Does it make any difference whether the earth is standing

still or moving around the sun?

[…]

In my opinion, it is not possible for religion to find a set of

metaphysical ideas which will be guaranteed not to get into conflicts

with an ever-advancing and always-changing science which is going into

an unknown. We don’t know how to answer the questions; it is impossible

to find an answer which someday will not be found to be wrong. The

difficulty arises because science and religion are both trying to answer

questions in the same realm here.

On the other hand, I don’t believe that a real conflict with science

will arise in the ethical aspect, because I believe that moral questions

are outside of the scientific realm.

The typical human problem, and one whose answer religion aims to supply, is always of the following form: Should I do this? Should we do this? Should the government do this? To answer this question we can resolve it into two parts: First — If I do this, what will happen? — and second — Do I want that to happen? What would come of it of value — of good?But therein lies the central friction — because of the

Now a question of the form: If I do this, what will happen?

is strictly scientific. As a matter of fact, science can be defined as a

method for, and a body of information obtained by, trying to answer

only questions which can be put into the form: If I do this, what will happen? The technique of it, fundamentally, is: Try it and see.

Then you put together a large amount of information from such

experiences. All scientists will agree that a question — any question,

philosophical or other — which cannot be put into the form that can be

tested by experiment … is not a scientific question; it is outside the

realm of science.

I claim that whether you want something to happen or not — what value

there is in the result, and how you judge the value of the result

(which is the other end of the question: Should I do this?), must lie outside of science because it is not a question that you can answer only by knowing what happens; you still have to judge

what happens — in a moral way. So, for this theoretical reason I think

that there is a complete consistency between the moral view — or the

ethical aspect of religion — and scientific information.

interconnectedness of all three parts of religion, doubt about the

metaphysical aspect invariably chips away at the authority of the moral

and inspirational aspects, which are fueled by the believer’s emotional

investment in the divine component. Feynman writes:

Emotional ties to the moral code … begin to be severelyHe concludes, appropriately, like a scientist rather than a dogmatist

weakened when doubt, even a small amount of doubt, is expressed as to

the existence of God; so when the belief in God becomes uncertain, this

particular method of obtaining inspiration fails.

— by framing the right questions rather than asserting the right

answers:

I don’t know the answer to this central problem — theThe Pleasure of Finding Things Out

problem of maintaining the real value of religion, as a source of

strength and of courage to most [people], while, at the same time, not

requiring an absolute faith in the metaphysical aspects.

Western civilization, it seems to me, stands by two great heritages.

One is the scientific spirit of adventure–the adventure into the

unknown, an unknown which must be recognized as being unknown in order

to be explored; the demand that the unanswerable mysteries of the

universe remain unanswered; the attitude that all is uncertain; to

summarize it — the humility of the intellect. The other great heritage

is Christian ethics — the basis of action on love, the brotherhood of

all men, the value of the individual — the humility of the spirit.

These two heritages are logically, thoroughly consistent. But logic

is not all; one needs one’s heart to follow an idea. If people are going

back to religion, what are they going back to? Is the modern church a

place to give comfort to a man who doubts God — more, one who

disbelieves in God? Is the modern church a place to give comfort and

encouragement to the value of such doubts? So far, have we not drawn

strength and comfort to maintain the one or the other of these

consistent heritages in a way which attacks the values of the other? Is

this unavoidable? How can we draw inspiration to support these two

pillars of Western civilization so that they may stand together in full

vigor, mutually unafraid? Is this not the central problem of our time?

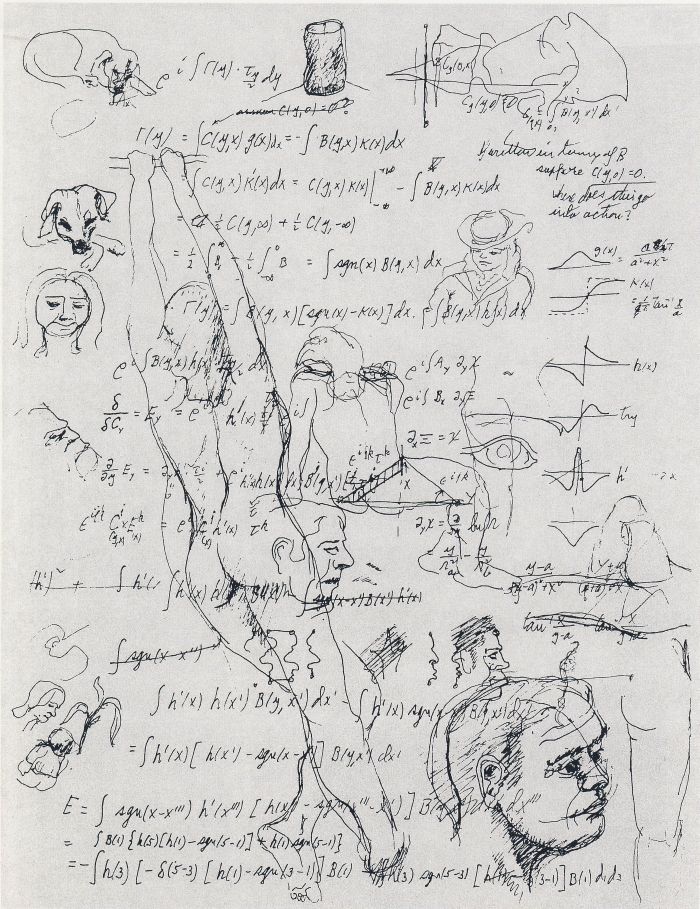

is a trove of the Great Explainer’s wisdom on everything from education

to integrity to the value of science as a way of life. Complement it

with Feynman on why everything is connected to everything else, how his father taught him about the most important thing, and his little-known drawings, then revisit Alan Lightman — a Great Explainer for our day — on science and the divinity of the unknowable.